[ 4 ]

The Emotional Aspect of Product Design

Shouting at the Voice Assistant

Back in 2016 I was working with the full-service advertising agency 72andSunny in Amsterdam and helping out on the launch campaign of Google Home in, among other countries, the UK. Fast-forward to 2019, and Google Home is now an integrated part of my own family’s home life. Even our daughter, who was born in the summer of 2017, knows what Google Home is because of the voice command “Hey Google.”

Many of the scenarios and use cases that we identified as part of the launch campaign apply to my family. Our primary use of Google Home right now is for simple things, like asking it to play music on Spotify, or to make various animal and vehicle sounds, to our daughter’s delight. But life can get complicated, and at times Google Home adds to that. Sometimes the really simple things don’t work, like Google Home misunderstanding “Turn up the volume” for “Turn off the volume,” or failing to hear when we ask it to turn off the music or turn down the volume. That causes the emotions in us to rise, particularly when things are already a bit hectic, or we’re tired.

During the launch campaign work, we kept the scenarios fairly high-level, as that’s all that was needed. Had we worked on the actual software for Google Home, it would have been a different matter. When you’re working with technologies that use sound as the primary UI for both input and output, you need to go into detail to understand scenarios. For our daughter’s first Christmas, we stayed with friends in Malmö, Sweden. Their whole apartment was hooked up to Amazon Echo, and the easiest way to turn on and off the lights was simply to ask Alexa to do so. In 2017, when you asked Alexa to turn off the lights, she responded “OK” and then turned off the lights. At first this wasn’t a problem, but when it came to turning off the bedroom lights when my partner and the baby were asleep, Alexa’s verbal response wasn’t ideal. Not knowing the volume level of Alexa added another dimension to the problem.

Turning off the lights in your kid’s bedroom when it’s time to go to sleep, or changing the lights to a different color, was one of the scenarios that we’d identified for the Google Home launch campaign. It’s one of those things that when it’s new, it’s quite magical, and from a practical point of view, not having to get up can be really handy, especially when you have young kids. How that feature is implemented, however, needs careful consideration, and in my opinion, there is no need for a voice assistant to confirm using voice that it has turned off the light. The act of doing so is evidence enough.

There is some talk about how VR and AR will influence both the experience of users and storytelling overall, but also how we as designers can experience what we design. Traditionally, whether we’re designing, watching a movie, or listening to a concert, we’re used to being the observer looking in. The fourth wall is there between us and what goes on behind the screen or on stage. With AR and VR in particular, we’re placing ourselves in the middle of the story and the experience, and increasingly it will feel like we’re there and part of it. Studies have shown that our bodies can’t tell the difference between a thought and an actual experience in the way it responds. Our senses are easily fooled, and if we feel joy and happiness, our bloodstream is flooded with endorphins; if we feel fear, adrenaline is released into our bodies.

At every single point of the experience with your product, even if it doesn’t include AR or VR, users go through emotions—from frustration (like that most of us have around passwords, or when we can’t find what we’re after, or something simply doesn’t work), to happiness (when it just works seamlessly, without any problems, as if the website or app we were using knew exactly what we wanted). Whether it’s a user using our products and services, an internal team member going through our work, or a client listening to us presenting it, in every kind of experience, emotions are involved and play a big part. Just as they do in stories.

The Role of Emotion in Storytelling

All the way back to ancient times, when storytelling was used to explain everything from natural phenomena to the adventures of a tribe, stories were told with a purpose. They might aim to calm and reassure people that after rain comes sunshine, or to help the rest of the tribe that wasn’t there to relive a battle and make sure they never forgot about important events. Each novel, movie, TV series, or play has a story to tell and a desired emotional response that it wants to evoke in its audience, and it’s the storyteller’s job to do so.

In the words of Daniel Dercksen of the Writing Studio, “The storyteller is the puppet master of emotion.” He writes:

As a writer you have the power to make your audience laugh whenever it pleases you, cause grown men to cry shamelessly, keep millions on the edge of reason, prevent couch junkies to switch channels, and grip people with fear.1

Evoking the audience’s emotions lies at the heart of storytelling, and without that emotional connection, there wouldn’t be a story to talk of. Writers and storytellers have numerous ways to capture the audience’s attention and pull them to the edge of their seats;―for example, through the way the story is told, or by it including suspense, tension, and conflict. But―the most powerful way to create an emotional connection is through the characters themselves. Just think back to some of the movies, books, or plays that have left a long-lasting impression on you; it’s the characters and their destiny that engaged you.

Emotion also plays a role in making that story come to life for the storyteller(s). Meg LeFauve, an American screenwriter, talks of how in the making of Pixar’s movie Inside Out, the personification of the emotions (Joy, Anger, Sadness, Fear, and Disgust) were already designed when she came on, which meant that she could see Riley, the girl who the emotions belonged to. The fact that the voice artist of Joy had also already been cast as Amy Poehler added another layer to the character that in LeFauve’s case, meant that she could really write to Poehler.2 Writers are often advised to draw from their own, or at least real, experiences when it comes to finding inspiration and giving the story depth. Being able to relate themselves is an important aspect in making sure that the story they’re writing will create an emotional connection with its audience.

As for product design, having empathy for the users we’re designing and building our products and services for is an important aspect, and we’ll touch more on that in Chapter 6, “Using Character Development in Product Design.” In this chapter, however, we’re going to focus on why striving to elicit certain emotions in design, otherwise known as emotional design, is so important in order to create a better experience for users.

The Role of Emotion in Product Design

In the early days of personal computing and human-computer interaction, the focus was on usability, functionality, and improving processes. More recently, there has been a shift toward also considering the emotional side. This change is to a large extent thanks to the thought leadership of Don Norman, a researcher, professor, and author of Emotional Design (Basic Books, 2004) (Figure 4-1), and Aaron Walter, author of Designing for Emotion (A Book Apart, 2011).

Emotional Design was in part a response to critics who argued that if they followed his advice in his earlier book, The Design of Everyday Things, products would be functional but ugly. Norman didn’t mention emotion in the first edition of The Design of Everyday Things. Instead, he focused on utility and usability, function and form in a logical, and in his own words, dispassionate way. In Emotional Design, he explores the profound influence that feelings and emotions have on us and how these are evoked through everyday objects.

Figure 4-1

Norman’s Emotional Design with the infamous Juicy Salif citrus squeezer on the front cover

A big theme of the book is that much of human behavior is subconscious and that consciousness comes later. If you look at how we react to a situation, he writes, we usually react emotionally before we assess the situation cognitively, and when most of us are asked why we decided on something, we often don’t know why. We just “felt like it” or “it felt good.”

Let’s explore the role of emotions in design and how storytelling can assist.

The Effect of Emotions on Decision Making

The role of emotions in decision making is well researched in marketing as well as in psychology. Antonio Damasio, professor of neuroscience at the University of Southern California, writes in Descartes’ Error that emotion is a necessary ingredient for almost all decisions. When we need to make a decision, our emotions from previous related experiences affect how we perceive our options, eventually leading us to create preferences.3 This is similar to the positive feedback mechanism and Freud’s pleasure principle, which states that we instinctively seek out pleasure and try to avoid pain by re-creating previously pleasurable experiences and avoiding situations that we consider likely to cause pain.

Many of us believe that the decisions we make are carefully considered and rational. We also often assume this approach when thinking through the actions a user might take in the experiences that we design. While this may sometimes be the case, often what sways us one way or the other in our decision making is our emotional response to what we’re experiencing. Take, for example, why we sometimes choose a specific, more expensive brand over another, or even the more generic and cheaper store brands. This is where our emotions come into play. A brand “is nothing more than a mental representation of a product in the consumer’s mind.” We create our own stories around everything that we experience, and when it comes to us evaluating brands, we primarily base it on our personal feelings and experiences rather than on information, features, and facts.

Positive emotions are also what influences brand loyalty to a larger extent than, for example, trust. As was the case with both the first iPod and the latest version of the iPhone, positive emotions are also what makes us buy certain products over others, even if they aren’t always the most practical ones, like Philip Starck’s iconic Juicy Salif that’s on the cover of Emotional Design.

Without emotions, our decision-making ability would be impaired and we wouldn’t be able to decide between alternatives, especially choices that appear equally valid.

The role of affect and cognition on decision making

When it comes to our everyday decision making, emotion and affect are crucial. Affect and cognition are both information processing systems, but with different functions. The affective system responds quickly by making judgments on whether things in the environment are dangerous or safe, good or bad. It’s our lizard brain, and the responses can be either conscious or subconscious. The cognitive system, on the other hand, interprets and makes sense of the world. Where emotion comes in is in the conscious experience of affect combined with the attribution of its cause and the identification of its object.

Both affect and cognition influence one another. In some situations, the affective state is driven by cognition, but most of the time cognition is impacted by affect. The example Norman uses to illustrate this relationship is that of a plank. If I place a plank on the ground and ask if you can walk on it, the answer will be a resounding “Of course I can!” If, however, I place it a hundred meters up in the air and ask the same question, the answer will be very different. What this example illustrates is that the affective system works independently of conscious thought. The visceral level, what we feel deep down in our gut, of looking one hundred meters down wins. Fear dominates our response rather than the reflective part of our brain that may try to rationalize that it’s the same 10-meter-long, 1-meter-wide plank, so of course you can walk it.

This is similar to the way we react when we watch a scary movie, or the way we feel after having watched one. Our cognitive system can rationalize and tell us that there’s a 99.9% certainty that no one is hiding in the darkness of the room, but what we’ve just seen and the emotions that are evoked in us may at times stop us from walking into that room without the lights on.

The coupling between our emotional and behavioral systems

Our emotional system is so tightly coupled with behavior and preparing our bodies to respond, Norman says, that the reactions we feel to any given situation are real manifestations of the way our emotions control our muscles and, for example, our digestive system. We have these same reactions when we’re subject to a story. Whether it’s in response to a story or an online experience, be it good or bad, something that makes us tense or relaxed, our emotions pass judgment and prepare our bodies accordingly, and the conscious, cognitive self observes these changes.

In response to our emotions, neurochemicals are sent to particular parts of our brain, changing our parameters of thought. What scientists now know is that affect changes our operating parameters of cognition, with positive affect enhancing creative, breadth-first thinking, and negative affect focusing our cognition as well as enhancing depth-first processing while minimizing distractions. This means that stress has a negative impact on people’s ability to cope with difficulties and to be flexible in how they approach problem-solving and that, to the contrary, positive affect makes people more tolerant.

Evidence also shows that aesthetically pleasing products work better and that when people are in a relaxed situation, pleasurable aspects of a design can make them more tolerant of difficulties and problems. Although poor design is, in Norman’s words, “never excusable,” good human-centered design practice becomes more essential for tasks or situations that may be stressful and where distractions, bottlenecks, and irritants in general need to be minimized.

The Influence of Emotions on Taking Action

One of the most interesting things about emotions is that they push us to action. We might have a fight-or-flight response if we feel afraid in a physical confrontation. Daily social situations that elicit desire or insecurity may lead us to buy the latest iPhone. Or our emotional responses might simply determine how we click or tap our way through a website or app. As we covered in Chapter 1, storytelling has been used throughout history to move people to action, from sparking our imagination to getting behind a cause. And that’s all caused by the emotions they evoke in us.

When you look at what influences purchase decisions, research shows that the emotional response to the content is more influential than the content itself. What this means for brands is that you need to ensure that you hit the right level of emotional resonance, at the right time. In other words, you connect with your potential customers on the right emotional level.4

However, understanding the impact of our emotions on our actions is just as much about understanding why we decide not to take action. Alessandro Suraci, a visual designer at Google, writes about how commitment is hard and that when it comes to setting goals and working toward achieving them, actually doing so is often further afield than the excuse for not doing what you’ve set out to do.5 As UX designers, we need to know the typical situation narrative and what users are feeling in order to understand how to move them into action, including what’s holding them back from following through.

|

[ TIP ] This exercise is particularly useful in relation to mapping out plot points and visualizing the shape of an experience, as we’ll cover in Chapters 5 and 9, respectively. |

The Influence of Emotion on Brand and Product Perception

Emotions also play a critical role in our long-term memory and our ability to understand and learn about the world. It’s one of the reasons storytelling has become such a buzzword, not the least in marketing. Marketing that includes the kind of storytelling that tugs on your heartstrings is more effective than any other type of marketing.

The reason for this increase in efficacy is that emotional storytelling is memorable. It creates deep connections that makes it harder to forget the message. Emotional storytelling also creates positive associations with the brand in question by linking positive images with the objective behind your marketing campaign. And last, marketing that involves emotional storytelling appeals to emotions instead of reason and gives the user an experience.

When you think about it, it’s a given. Very few of us will remember an OK movie or book, but we remember the really good or bad one. It’s the same when it comes to the products and services that we use. We remember the ones that caused us massive frustrations and the ones that brought us joy. More often than not, the ones on either side of the spectrum are the ones we talk to others about and the ones we tend to write a good, or a bad, review of.

|

[ TIP ] This exercise can also be carried out internally among team members, internal stakeholders, and with clients, and help form the foundations of hypotheses that can later be tested. |

Emotions and Our Different Levels of Needs

Aaron Walter, the author of Designing for Emotion, defines emotions as the “lingua franca of humanity,” the native tongue that all human beings are born with, and says that emotional experiences are critical to our long-term memory. When it comes to design, an emotional response makes the experience feel like there’s a human being on the other side rather than just a machine.6

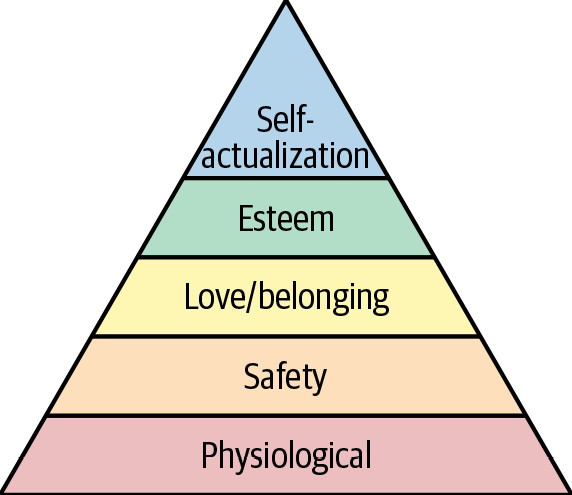

In his book, Walter has developed a pyramid of user needs that draws on Maslow’s pyramid of needs. The latter was developed in 1943 and included in his paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” (Figure 4-2). Maslow posed that, as human beings, we have basic needs (like physiological ones), that have to be met before more advanced needs (like self-actualization), can be addressed.

Figure 4-2

Maslow’s pyramid of needs

If the four most basic needs, which Maslow calls deficiency needs, or d-needs, aren’t met, the individual will feel anxious and tense even if there is no physical sign. This has some interesting parallels with design. If we map this insight from Maslow’s pyramid over to interface design, Walter says, we can “get a better understanding of the way our audience works.”

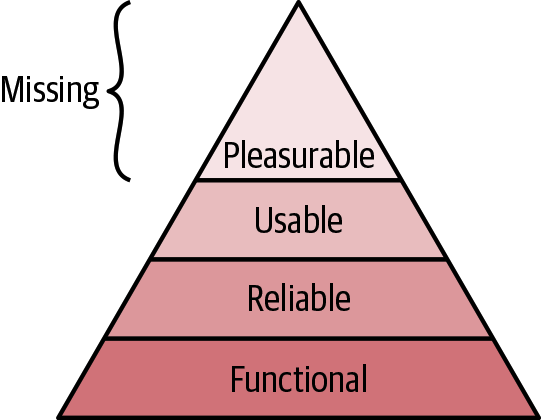

Just as with Maslow’s pyramid of needs, the four basic layers have to be met in Walter’s pyramid of user needs before the user can appreciate the pleasure layer (Figure 4-3).

Figure 4-3

Walter’s hierarchy of user needs states that basic user needs must be fulfilled by the interface first before more advanced needs can be met

Walter’s theory suggests that the first thing we have to do with our products and services is to address the functional layer and ensure that we solve a problem for our users. After that, we have to make sure that what we design and build is reliable and usable, meaning easy to learn, easy to use, and easy to remember. What we often overlook, however, according to Walter, is the pleasure layer that comes next.7

Pleasure in Design

The pleasure layer is where we have an opportunity to take the user experience to the next level. What we normally talk about in design as delights aren’t just the gimmicky things that will get you a mention in the press, but the small touches that help make the user connect on an emotional level. Delightful details can be as simple as an animation or the illustrations that accompany many of the Install Application dialog boxes on a Mac.

Delights, however, are so much more than that. They are also in the overall feel of an experience, or how you move seamlessly without any delays from one screen to the next, the animations and transitions that are being used, as well as the use of micro copy and iconography throughout, to mention a few examples.

Walter refers to these delights as pleasures, and draws a great parallel to eating out. We go to a fancy restaurant, we don’t just hope for an edible meal. We hope for much more. We hope that the food will be amazing, that the ambiance and service will be great, and that the whole experience will be memorable. Walter argues that we shouldn’t settle for just usable in design when we can create designs that are both usable and pleasurable.

Walter defines two types of delights within the pleasure layer:

Surface delights

These delights are local and contextual and often derived from isolated interface features like animations, gestural commands, micro copy, high-resolution imagery, or sound interactions.

Deep delights

These delights are holistic and are achieved only when all the user needs are met and the user has reached a state of flow with little distraction from the main task.

Deep delights are much harder to accomplish than surface delights. Even if users have a poor overall experience, they may still experience some surface delight. Deep delights, on the other hand, are experienced only when things work just the way they should and deliver everything as expected without getting in the way; a bit like the magic of a good story, where everything just comes together.

It’s when users experience deep delights that they are most likely to recommend a product or service to their friends, families, and colleagues. While they might be less sexy from a design point of view than surface delights, deep delights are the ones to get right first and foremost, after the lower-level user needs are met, just as with Maslow’s pyramid of needs.8

Addressing the Lower-Level Needs First

As Norman points out, positive affect makes people more tolerant of difficulties or problems. While many of the emotions we’re hoping to ignite with our users would fall under the pleasure layer, plenty of emotions can be evoked on the lower levels, many of them negative if we fail to deliver on the most basic level. John Maeda, an American executive, designer, and technologist, talks about complexity and simplicity and suggests that the latter is “about living life with more enjoyment and less pain.”9 New York Times columnist David Pogue started out a TED talk by singing out his frustrations around technology and being on hold with customer service before going on to talk about software rage.10

We’ve all been there and know that when technology doesn’t work, or when websites make it difficult to do what we want, or when voice assistants add to the chaos as mentioned at the beginning of the chapter, it can send emotions as strong as rage through our bodies. But even if it’s not rage we feel, everyday frustrations caused by technology are more than enough. The passwords of a family member are a funny tribute to the frustrations of using technology. Hardly any of them are what you’d expect. Instead they might include swear words and any other imaginative words along the same lines. The passwords say more than a little about what that person thought of passwords.

As much as we might be excited to work on areas and experiences of the product that fall under the pleasure level, we have to make sure, as Walter points out, that we have first addressed the most basic levels of needs. It doesn’t matter how beautiful a website or app is if it isn’t functional or doesn’t have a purpose. And if it’s functional but not reliable, it will leave users frustrated. Equally, if a product requires a lot of effort to use, or to learn how to use, it won’t be considered very usable. It’s only when a product is functional, reliable, and usable that users can appreciate the delightful and pleasurable aspects of the product. We need to get the basics right, and what constitutes “basic” is constantly evolving.

The Strive for Constant Betterment and the New Normal

One of the other things Maslow posed in his theory of human motivation is that we strive for constant betterment and seek to go beyond the scope of the basic needs. Metamotivation, as he calls it, is something we should keep in mind in design. When the first iPhone came out, we didn’t think much about how websites appeared as they were on a desktop, but smaller, in our phones. However, when we started developing mobile sites, we became more accustomed to mobile-optimized solutions, and these gradually became the norm and something we expected.

What this “new normal” illustrates is that when it comes to development in technology and the products and services that run on them, the goal post for what constitutes functional, usable, reliable, and pleasurable moves as our devices become more advanced and user behavior changes. Being able to do the same things on our phones as we can do on our desktops is no longer something that we’d say would fall in the pleasure layer, as it did in the early days of the mobile web. Instead, it’s the new normal and part of the functional layer of the product. This constant need to adapt to technological advances and strive for betterment is why understanding user expectations and emotions are so closely tied and important in product design.

Understanding Emotions

Just as a good story, whether it’s a film, book, or play, connects with us on more than the visual level, the appeal of products is about more than how they look. Steve Jobs famously said, “Design is not just what it looks and feels like, it’s how it works.”11 Author Cindy Alvarez says that she’d like to go one step further and say, “Design is how you work. [It’s] how you feel when you are using things or having experiences.”12 While products and services, like those of Craigslist or Amazon, for sure can and do work, design and the UX of the same are increasingly becoming competitive factors, and emotional design plays a key part. Design thinking and experience design as well as customer experience, otherwise known as CX, have increasingly become well known, and for good reason.13

When the first iPod came out in 2001, it made a big impact. That wasn’t just because of the enormous number of songs it could hold, but also because of its design with the iconic white headphones and scroll wheel. Bruce Claxton, then president of the Industrial Designers Society of America, has said, “People are seeking out products that are not just simple to use but a joy to use.”14 The iPod was both seductive and simple to use, and it connected with users on an emotional level.

Three Levels of Emotions in Relation to Product Design

According to Norman, when it comes to objects, we form connections on three levels:

The visceral level

This deals with aesthetics and the perceived quality of the product from its look and feel to the way it engages our senses. This level is closely related to our initial reaction (more precisely, that gut feeling) when we encounter a product.

The behavioral level

This refers to the usability of the product and our assessment of whether it performs the desired functions, as well as how easily we can learn to use it. At this level, we’ll have formed a more informed opinion about the product.

The reflective level

This concerns the impact we perceive the product to have on our lives. This level is about “after” usage; for example, how we feel after we’ve held a product and the values we attach to it in retrospect. This is where we’ll want to create as much desire as possible when it comes to product design.

Each of these three levels plays a role in shaping our experience of a product, but each level also requires a different approach by the designer. In order to provide and design for a positive experience, we should address the user’s cognitive ability on each level and put it into the context of the experience.

Types of Emotions

Norman’s three levels provide a great framework for thinking about emotions in relation to product design. But at times we need to go deeper than that and look at the types of emotions users experience when using our products in order to really help define the experience of the same.

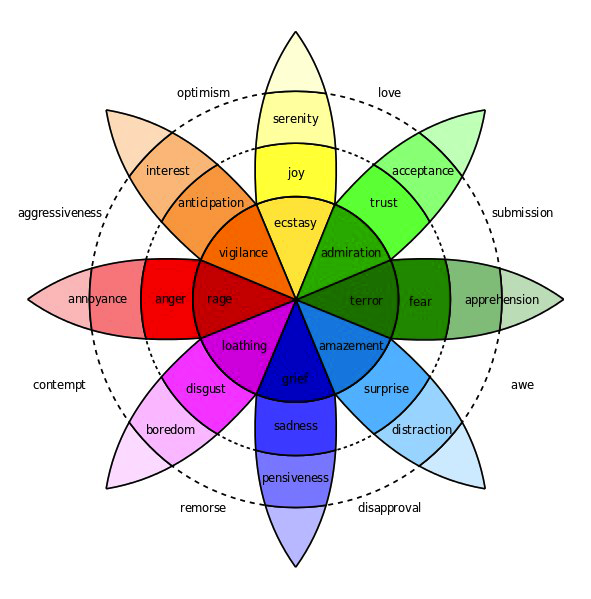

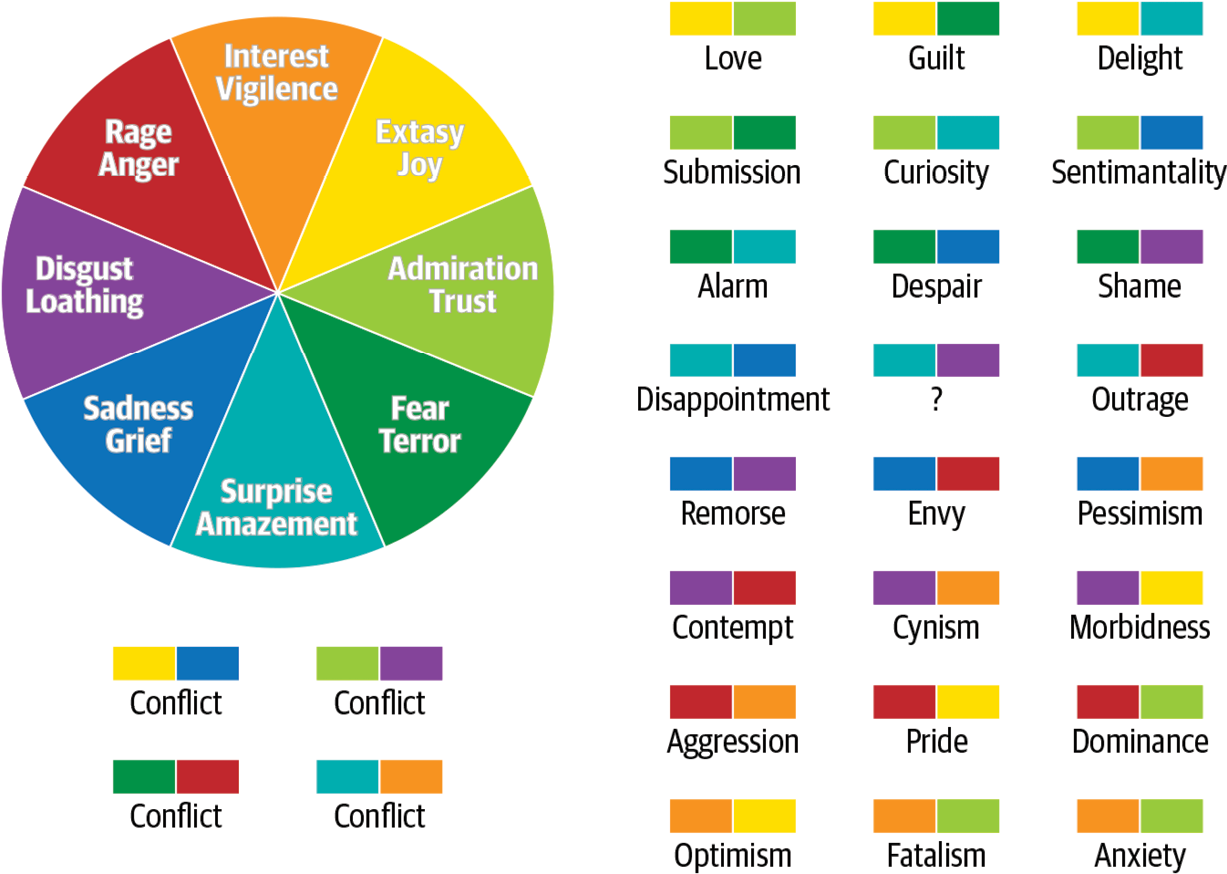

A good place to start is with Plutchik’s wheel of emotions (Figure 4-4). Psychologist, professor, and author Robert Plutchik devised one of the most influential classifications of general emotional responses in his psychoevolutionary theory of emotion, which categorizes primary and secondary emotions.15

Figure 4-4

Plutchik’s wheel of emotions

Primary emotions

Plutchik considered there to be eight primary emotions:

- Anger

- Disgust

- Fear

- Sadness

- Anticipation

- Joy

- Surprise

- Trust

He considered these “basic” emotions to be the ones that have evolved in order to increase the chance of survival.

Secondary emotions

As part of his psychoevolutionary theory, Plutchik also defined 10 postulates, one of which is, “All other emotions are mixed or derivative states; that is, they occur as combinations, mixtures, or compounds of the primary emotions” (Figure 4-5).

The secondary emotions are as follows:

- Anticipation + Joy = Optimism (its opposite being Disapproval)

- Joy + Trust = Love (its opposite being Remorse)

- Trust + Fear = Submission (its opposite being Contempt)

- Fear + Surprise = Awe (its opposite being Aggression)

- Surprise + Sadness = Disapproval (its opposite being Optimism)

- Sadness + Disgust = Remorse (its opposite being Love)

- Disgust + Anger = Contempt (its opposite being Submission)

- Anger + Anticipation = Aggressiveness (its opposite being Awe)

Understanding the nuances of emotions, their opposites, and the makeup of each emotion is useful when going into detail on what emotional responses we are evoking, and which ones we would like to evoke in the products and services that we design. As with all stories, if we’re clear on the outcome we’re after, it’s easier to identify the right principle, tool, or method to make it happen.

.

Figure 4-5

Plutchik’s mixture of primary emotions into combinations and opposites16

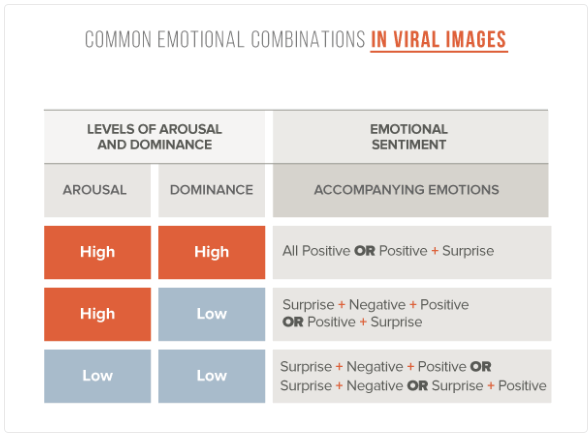

What Makes Us Share

As Plutchik’s wheel of emotions demonstrates, emotional responses aren’t always positive feelings. Although most of the experiences we design seek to evoke positive feelings, at times the opposite drives our behavior. Viral content, for example, can thrive on negative emotions. For instance, on YouTube, a lot of funny videos go viral, but so do also a lot of angry political rants. Whether they’re funny, heartfelt, or angry rants, what these videos have in common is that they contain triggers that get people talking.

Andrea Lehr, a Promotions Supervisor at Frac.tl, wrote about the role of emotions in shareable content and referenced a study carried out on one hundred viral Reddit images. “The dress” of 2015 that had the internet going mad about whether it was gold or blue is one of her examples of something seemingly pointless that influenced behavior. The seller of the dress saw its organic traffic increase by 420% and sales of the dress increase by 560%, all because an image of it went viral. So what is it, then, that makes people share it?17

Lehr’s research found that virality is a combination of emotional connection paired with additional dimensions of arousal and dominance. The top emotional responses to viral images are as follows:

- Happiness

- Surprise

- Admiration

- Satisfaction

- Hope

- Love

- Happiness for

- Concentration

- Pride

- Gratitude

While negative emotions like hate, reproach, and resentment were far less common in viral content, they can still play a role as long as they hit the right combination of arousal and dominance. Lehr refers to additional research carried out on the roles that valence, arousal, and dominance play on generating viral content and defines them as follows:

Valence

The positivity or negativity of an emotion

Arousal

Ranges from excitement to relaxation, with anger being a high-arousal emotion and sadness low-arousal

Dominance

Ranges from submission to feeling in control, with fear being low-dominance and admiration high-dominance

When the research team mapped arousal and dominance levels against the one hundred viral Reddit images that they analyzed, they found that the three combinations shown in Figure 4-6 are more successful in generating shareable and viral content.18

Figure 4-6

Lehr’s identified common emotional combinations in viral images

Creating a viral marketing campaign, or content in any form, is the dream of many brands, startups, marketers, and aspiring influencers. Understanding the underlying emotional sentiments and the combinations that are most likely to produce the desired effect is a powerful tool to apply to both marketing campaigns and product design in general. By being clear on what we’re trying to evoke, and why, we have a better chance of accomplishing our objective. Next we’ll take a look at some situations where emotions play a particularly important role.

Situations Where Emotion in Design Can Play a Key Role

As we covered earlier in this chapter, good design practices are particularly important in parts of any experience that may be deemed stressful or more complicated. In these situations, aesthetically pleasing design alone won’t be enough for us to forget the stress we might feel concerning the task at hand, whether that’s filling out a form, finding critical information, or placing an order. As both Norman and Walter point out, design needs to be usable as well.

Understanding how emotions play a particular role in the experience with a product or service is an important step in helping define and design the right experience of and around that product. In Chapter 5, we’ll look at narrative structures and key points in an experience. However, as background for that, we’ll take a look at some particular situations and moments where emotion in product design matters.

Categorizing Product Experience Moments as Happy, Unhappy, Neutral, or Reflective

When looking at the various situations and moments in product design where emotions can play a key part, I group them into four categories: unhappy, happy, neutral, and reflective.

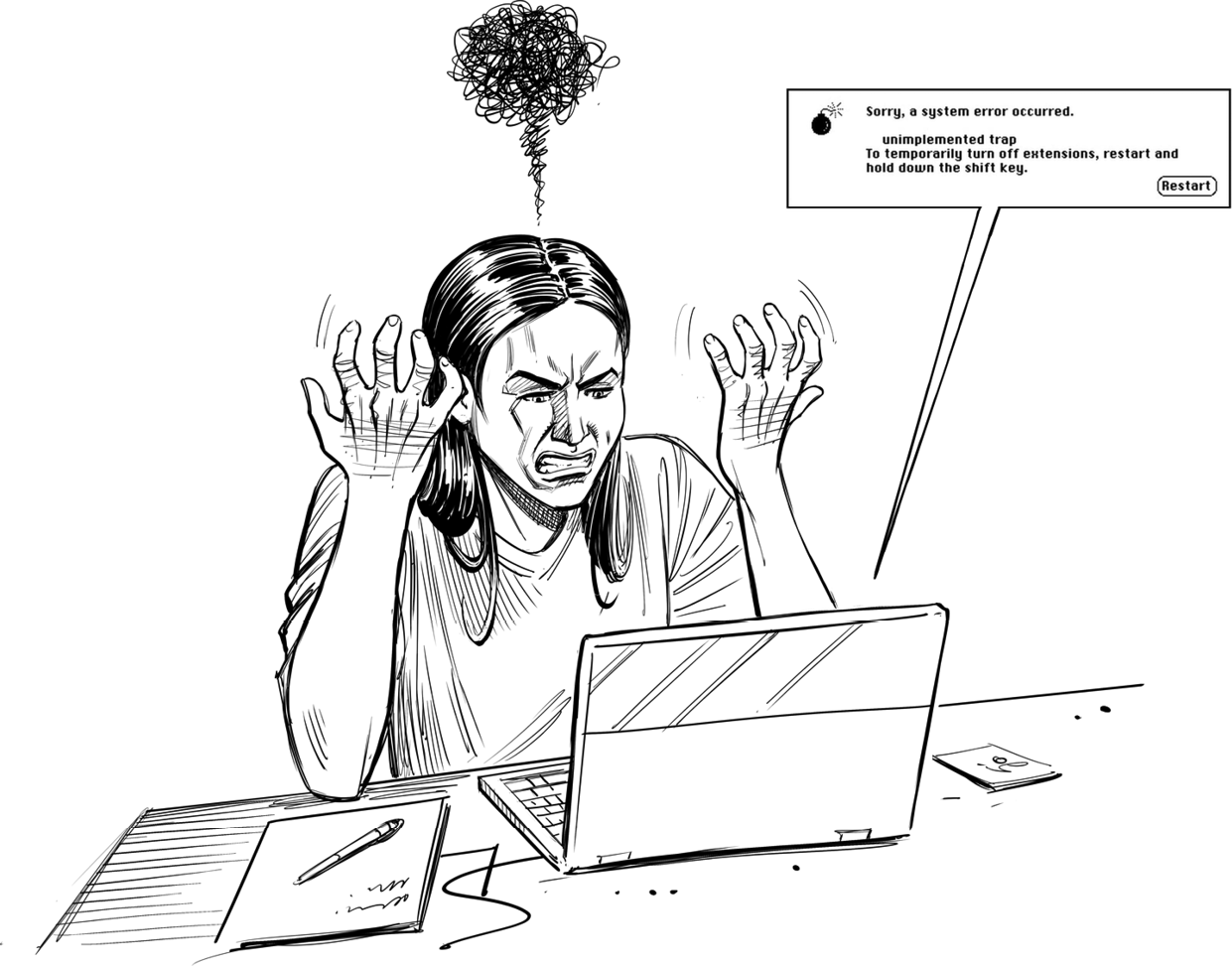

Unhappy moments

Unhappy moments are those that a user would rather be without, skip, or avoid altogether (Figure 4-7). They’re often the hygiene features and steps in a journey that have to be completed when users carry out a task, and the moments when things don’t go the way they expect.

Figure 4-7

Unhappy moments in product design

Examples of unhappy moments are as follows:

Barriers

Creating an account, logging in, making a payment, filling out long forms, making a selection

Usability issues

Unclear CTA, unclear usage, confusing information architecture (IA), wrong use of language

Errors

404 pages, error messages

Referring back to Plutchik’s wheel of emotions, some of the emotions that the user may experience here are anger, annoyance, apprehension, disapproval or even rage, loathing, sadness, remorse, and fear.

With regard to Norman’s three levels of emotions, unhappy moments primarily fall under the behavioral level. The visceral level and the reflective level also come into play in terms of our first impression and the overall feeling it leaves us with.

Happy moments

Happy moments, on the contrary, are moments that should either be positive (e.g., after a user has completed a task), or moments in which the user is pleasantly surprised (Figure 4-8). They can also be moments where you’ve identified that, compared to your competitors, you want to stand out and create a memorable experience for the user through added delights.

Happy moments can range from a little happy to very happy. Here are some examples of moments that can or should be happy:

First impressions

Onboarding, landing pages

Task completions

Confirmation pages and messages

Physical deliveries

Unboxing experiences

Delights

Explicit use of personality, animations, imagery

These happy moments often evoke the following emotions in the user: amazement, interest, anticipation, joy, love, optimism, and surprise. They primarily concern Norman’s visceral and reflective levels.

Figure 4-8

Happy moments in product design

Neutral moments

Though we want to avoid unhappy moments, as we’ll cover in Chapter 9, not every moment in an experience can, or should be, a happy one. Some moments need to be neutral and not ask anything of the users, but instead let them go through the experience with very little cognitive load (Figure 4-9). Neutral moments aren’t just important to help minimize the cognitive load for the user. They are also essential in creating contrast to happy and reflective moments.

Though the circumstances and context surrounding the following listed examples can change them from neutral to unhappy, happy, or reflective moments, these are some examples of neutral moments:

Day-to-day tasks

Answering emails, checking Slack

Researching

Noncomplicated searches, such as for opening times or menus

Carrying out a task

Form completion (unless barriers are encountered)

Trust, acceptance, as well as more moderate levels of optimism, interest, and joy are examples of emotions that a user may experience in relation to neutral moments.

As for Norman’s levels of emotions, neutral moments primarily deal with the behavioral level with regard to ease of use and usability.

Figure 4-9

Neutral moments in product design

Reflective moments

Reflective moments are moments that should intentionally be designed to add friction in design, according to Per Axbom, a coach, designer, and writer (Figure 4-10). In contrast, neutral and happy moments should encourage flow and action in the user’s task completion or experience of the product. This friction is not necessarily meant to stop users, but instead look after them by ensuring that the decisions they make and actions they take are decisions and actions they want to take, and will be happy to have taken afterward.

Figure 4-10

Reflective moments in product design

Here are some examples of reflective moments:

Parting with data

Permissions

Parting with monetary value

One-off payments, subscriptions, selecting payment options

Termination

Canceling a service or subscription

Contributing

Commenting, uploading, submitting

Confirming

Choosing delivery address or date/time

With regard to Norman’s three levels of emotions, reflective moments are a bit of an outlier in that, though they concern the behavioral and visceral levels of emotions, they should also activate the reflective “after” usage level while in the moment.

As with Walter’s pyramid of user needs, there is little point in focusing on the happy moments—for instance, adding pleasures and delights to add to the experience—before the other categories of moments have been identified.

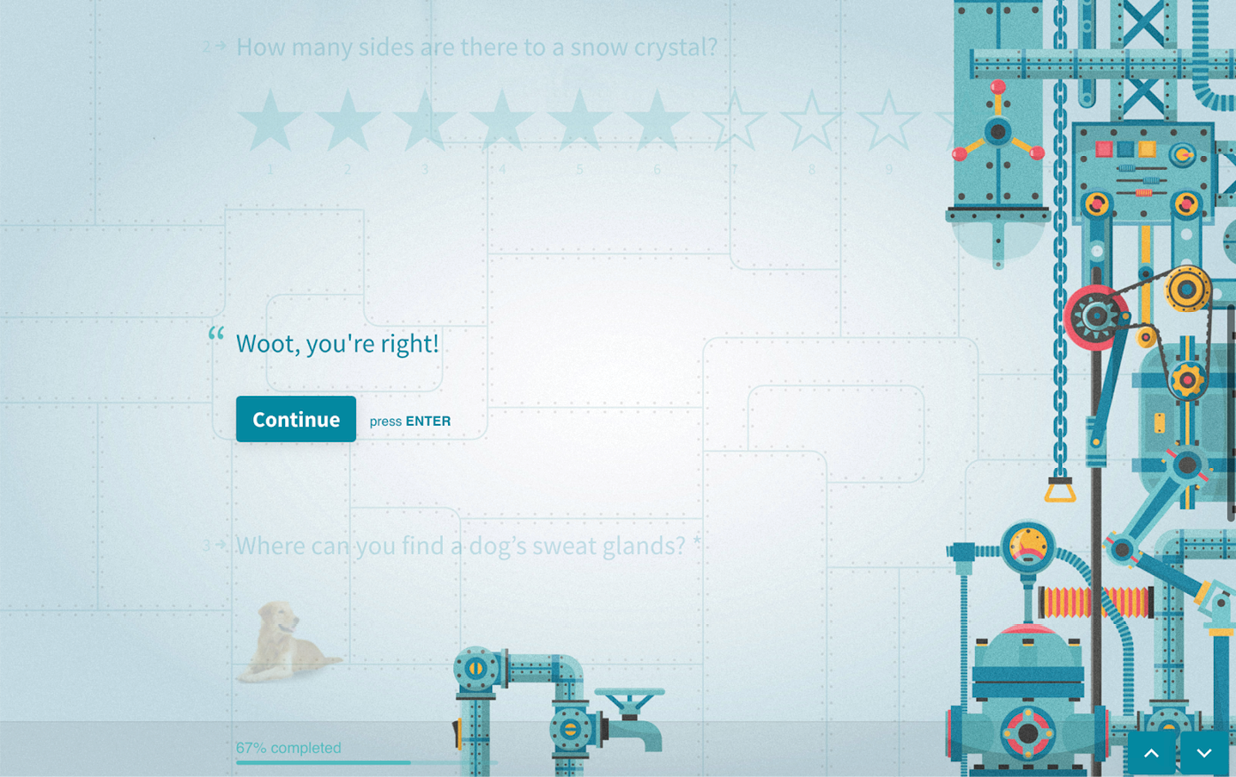

Though the preceding categorization is a generalization, in some instances, depending on the specifics of a product or service, a moment that I’ve categorized as neutral should have more focus as a happy moment, or vice versa. An example of this is an Amazon confirmation page after purchase, which does very little to evoke happiness, but instead functions more as utility. Another example is Typeform, an online form and survey builder tool. Typeform focuses on adding more delight and ease of use into the user experience of completing and creating its forms and surveys (Figure 4-11).

Which category situations and moments will fall in, and what type of emotions certain parts of the experience should evoke in your users and customers, will always come down to the specifics of that product or service as well as the objectives and goals you have with it.

Figure 4-11

The Impossible Quiz, one of the featured examples of the kind of form you can create with Typeform

Designing for Positive Emotions

Simon Schmid of Smashing Magazine says that we shouldn’t be afraid to show our personality in design, as long as it’s geared toward the right people.19 He outlines a nonexhaustive list of eight psychological factors, based on his own personal observations, that can help evoke positive emotions in design:

Positivity

Focus on the positive

Surprise

Do something unexpected or new

Uniqueness

Be different from other products and services in an interesting way

Attention

Offer incentives, or to help, even if you’re not obliged to

Attraction

Build an attractive product

Anticipation

Leak something ahead of launch

Exclusivity

Offer something exclusive to a select group

Responsiveness

Show the audience a reaction, especially when they don’t expect it

When it comes to applying these factors to design, or examples in design, there are often overlaps between them. How users will respond to them, he says, will vary based on who they are, their background, cultural factors, and more.

What Storytelling Can Teach Us About Evoking Emotions in Product Design

Just as certain techniques are used to evoke certain emotions in films, books, plays, and the design of physical experiences like exhibitions, there are methods and principles we can use to evoke specific emotions in design. In this section, we’ll take a look at five ways inspired by traditional storytelling that can help create an emotional connection with the end user.

Spark the Imagination

I came across an article by Joe Berkowitz, a writer and staff editor at Fast Company, that talks about how to tell scary stories. According to Berkowitz, “If you can imagine yourself in a situation,” he says, “it’s infinitely scarier.”20

Most of us have at some point watched a movie or TV show where the plot and how it’s brought to life did something to us—something made our heart beat faster; perhaps we pulled up our legs toward our chest, or covered our ears or our eyes. It’s those moments that Berkowitz is talking about where the movie or TV show has captured our imagination to the point where the storyline holds us in its grip. By the way the music changes, or the light goes slightly dimmer and darker, we can tell that something bad is about to happen. It’s usually not something we can put our finger on, but somehow we just know. Our anticipation grows and we’re on the edge of our seat, as any minute now, the killer may strike.

What makes something scary is, according to Berkowitz, often the not seeing. In the movie The Blair Witch Project, for example, you never see the force that is involved in the attacks. In the movie Jaws, you don’t see the shark until the Fourth of July weekend, which is more than halfway through the movie. Steven Spielberg had originally included the shark in the first scene of his script but because of mechanical errors was forced to use the shark very sparingly.21 What makes us relate isn’t just in what we can see. It lies in the overall emotional response.

This is something to keep in mind when it comes to the work we do. While we’re not out to scare our users or audiences, we are out to capture their imagination and their attention (Figure 4-12). We want to evoke emotional responses through the work and experiences we’re presenting, no matter what platform or technology we’re using. We want to place our users and audience in the middle and, not too different from the job of a writer, to present our version of the dramatic question in such a way that our audience and our users want the answer to be “yes.” We want our products and services to benefit and help users accomplish their goals and improve their lives, no matter how small the impact might be. Or, we want the idea or solution we’re presenting to internal stakeholders or clients to be just what they need.

Figure 4-12

Spark the imagination

Whether it’s our clients, colleagues, or users who are our audience, we want them to be able to imagine themselves in the picture we’re painting. But as UX designers, we too should be able to imagine ourselves in their situation.

Add Personality in Product Design

One of the ways we can evoke emotion in design is through the personality of the products and services we create (Figure 4-13). Walter argues that “personality is the platform for emotion.” It’s what we use to both empathize and connect with other humans, whether through laughter or tears. Similarly to the way babies learn to trust that their parents will come and soothe them when they need it, a feedback loop exists in interface design. Positive emotional stimuli can build trust and engagement with users over time, and this positive affect, as Norman pointed out, can make users more forgiving of shortcomings, or when things go wrong.22 Personality, however, is also an increasingly important element when it comes to the experience in general, the brand, and the overall narrative that it tells.

Figure 4-13

Add personality in product design

Some of the ways we can add personality in product design and evoke emotions are through the images, iconography, and animations that we use. These can convey literal emotions, such as people smiling in the images that are used, or a shopping cart icon smiling after you’ve added items to it, as on threadless’s website. Other ways are through copy and micro copy and the TOV that is used in them. As we’ll cover in Chapter 6, it’s becoming increasingly important to develop the character of the product or service that we’re designing and know how this behaves across different touch points and devices, and in different situations.

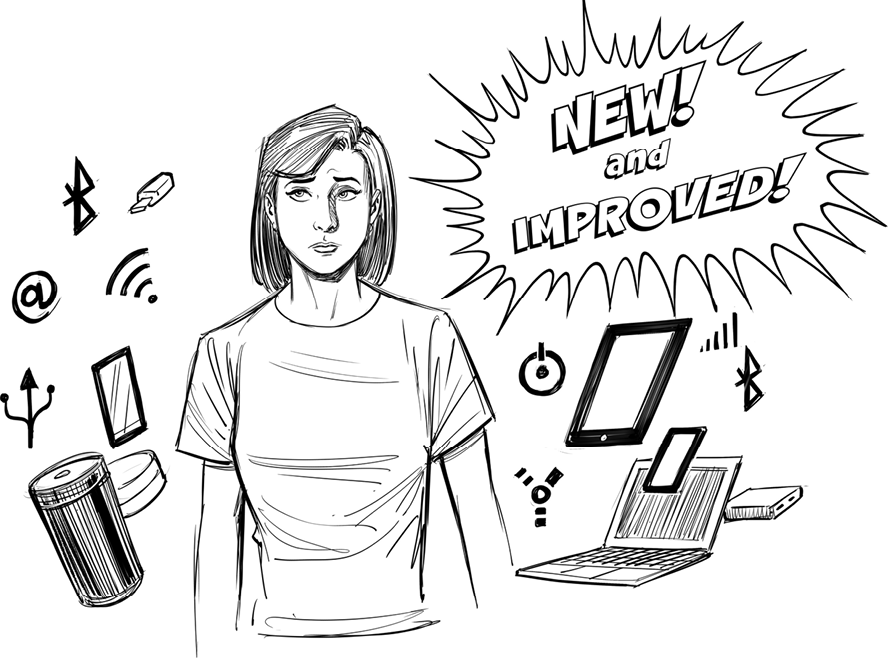

Focus on Outcomes Instead of Features

A great article by Hoa Loranger of the Nielsen Norman Group says that instead of focusing on features, we should focus on outcomes.23 At times there’s a tendency to focus a bit too much on the product we’re creating or specific features without thinking thoroughly about the problem we’re trying to solve. This, the problem, is the outcome, and the product or feature is the output. This distinction, the article argues, is related to the classic difference between a feature and a benefit. A feature is something that is offered by the product and service. The benefit is the value it offers to the user and what the user is actually after (Figure 4-14).

This benefit, if presented well, is closely related to story and, as we talked about in Chapter 1, the human mind processes facts differently when they are embedded in story. One of the oldest tricks in marketing is that you sell more if you focus on the benefits rather than the features. Similarly, when it comes to the products and services we design, Loranger argues, if we focus on the benefits we offer and how they solve users’ pain points, those users are more likely to pay attention than if we simply present a list of features.

Figure 4-14

Focus on outcomes instead of features

Make the Message About the User

In addition to focusing on features, we should focus our messaging on the user. However, “what companies know best will always be their products and services.” So starts an article by consultant Melanie Deziel about why brands need to branch out from product-focused content.24 Consumers and users generally trust companies to educate them on topics that are within their expertise, but as soon as that company includes a product-focused message, the credibility drops from 74% to 29%.25

Over the last few years, we’ve started to see more and more brands and companies moving away from self-promotional content and instead shift toward messaging that focuses on use of the product and service and the emotional aspect of how these make the consumer/user feel. Dove’s “Real Beauty” is one such example. Team America’s “Gold in the US” is another one.

As we talked about in Chapter 3, technology products and services are increasingly becoming about the needs and experience of the individual user rather than broader target audiences as a whole. Deziel talks about a ring of the personal, internal, and emotional reasons someone might use your product, and that the motivation for using it is driven increasingly by the feeling users get (or the lack thereof, for that matter). Squarespace, an all-in-one website-builder platform, is a good example, Deziel says. At the most basic level, Squarespace helps people share information about their business. But on a more emotional level, it empowers people to build something themselves, which in turn can help dreams come true (Figure 4-15). That’s the story the product-related messaging should be focused on.

Figure 4-15

Make the message about the user

Identify the “What if” of Your Products and Services

All good stories spark the imagination. The really good ones tap into the dreams and desires of their audience by raising the “What if…?” question that makes them feel that those dreams are actually attainable. Raising the “What if…?” question is something we can and should do in product design as well—but to do that, we need to start at where things are. When it comes to product design, we can’t focus only on the emotions we want users to feel. It’s equally important to consider what they might be feeling right now and what they felt before coming to us.

If you think back to Duarte’s TED talk, she says that listeners (or in this case, the users), might be fairly happy with the way things are right now. Perhaps they tend to use a competitor site of yours that isn’t perfect, but it works. Perhaps they’ve come to expect that forms or registration processes are a pain and expect nothing else. We need to take them to the elevated “What if” scenario. This scenario isn’t always posed as a question or call to action, but can be done through simply showing how it, and life as we know it, can be different (Figure 4-16).

Figure 4-16

Identify the “What if” of your products and services

I remember unpacking my first mobile phone in the late ’90s and having to charge it before it could be used. That was the norm. But, then Apple came along and delivered partly charged products that could be used straight out of the box. This was a simple we’re-going-to-show-you-how-it-can-be-done “what if” that soon had the other players in the market following suit.

The change was simple, yet it significantly changed the experience of the people who unpacked their products for the first time. As we covered earlier in this chapter, what we consider functional, usable, and pleasurable with regard to product design constantly moves. When new becomes the norm, as with Apple’s partly charged phone, and as more companies followed suit, consumer expectations shifted such that buyers now assume that the battery will be partly charged.

In order to innovate and to ensure that we deliver against the ever-moving goal post of what’s considered a functional, reliable, and usable need versus “pleasurable,” we need to identify what the partly charged battery is for our products and services. We need to dare to dream big and then figure out how to make that come true.

|

[ TIP ] This exercise is useful to do as a full end-to-end review of your experience/service design that uses a customer experience map, \ or a customer journey map. Work through the “What if…?” for each relevant step of the experience. |

Summary

As with everything we plan, design, and build, there are no guarantees that users will have the experience we hope they will have, or that they will feel the emotions we’re trying to evoke. In fact, we can almost be sure that it won’t happen exactly the way we planned. This chapter, however, has provided a deeper understanding of the emotional responses users will have throughout their experience with our product or service. By understanding the role of emotions as well as the types of emotions, and being clear on which ones we want to evoke at which points in the product experience and why, we’re one step closer to achieving both our goals and those of our users.

In addition to ensuring that the fundamental levels of Walter’s pyramid of user needs are met, we should also strive to identify where adding to the pleasure layer will benefit the user in the product experience. More often than not, designers are encouraged to add surface delights like animations, micro copy, or other visual elements. Though they can help with branding and creating personality in design, we should increasingly try to achieve holistic deep delights that help the user achieve flow—something that is closely linked to identifying the story we should tell with our product or service, which is what we’ll be looking at next.

1 Daniel Dercksen, “The Art of Manipulating Emotions in Storytelling,” The Writing Studio, February 22, 2016, https://oreil.ly/K1bxJ.

2 Joe Berkowitz, “7 Tips on Emotional Storytelling,” Fast Company, December 1, 2015, https://oreil.ly/yBG-l.

3 Peter Noel Murray, “How Emotions Influence What We Buy,” Psychology Today, February 26, 2013, https://oreil.ly/Hsfp4.

4 Andrea Lehr, “The Role of Emotions in Shareable Content,” HubSpot (blog), https://oreil.ly/ImfOe.

5 Alessandro Suraci, “Picture a Better You,” Medium, April 13, 2016, https://oreil.ly/c3T9J.

6 Aarron Walter, “Emotional Interface Design,” Treehouse, August 7, 2012, https://oreil.ly/PBC5y.

7 Walter, “Emotional Interface Design.”

8 Therese Fessenden, “A Theory of User Delight,” Nielsen Norman Group, March 5, 2017, https://oreil.ly/X7xwX.

9 John Maeda, “Designing for Simplicity,” TED2007 Video, March 2007, https://oreil.ly/O074K.

10 David Pogue, “Simplicity Sells,” TED2006 Video, February 2006, https://oreil.ly/ExNFa.

11 Rob Walker, “The Guts of a New Machine,” New York Times, November 30, 2003, https://oreil.ly/Z8Qyk.

12 Mary Treseler, “Design Is How Users Feel when Experiencing Products,” O’Reilly Design Podcast, August 20, 2015, https://oreil.ly/Z3SMH.

13 Manita Dosanjh, “Building Magic Moments,” The Drum, August 5, 2016, https://oreil.ly/Bdb37.

14 Walker, “The Guts of a New Machine.”

15 For more on Plutchik’s wheel of emotion in relation to putting emotions into your designs, visit the Interaction Design Foundation (https://oreil.ly/-gJtl).

16 Interactive Design Foundation, https://oreil.ly/yGGjL.

17 Andrea Lehr, “The Role of Emotions in Shareable Content,” HubSpot (blog), July 20, 2016, https://oreil.ly/t_Ehr.

18 Lehr, “The Role of Emotions.”

19 Simon Schmid, “The Personality Layer,” Smashing Magazine, July 18, 2012, https://oreil.ly/dvEcV.

20 Joe Berkowitz, “How to Tell Scary Stories,” Fast Company, October 31, 2013, https://oreil.ly/GupTC.

21 Watch “The Making of Jaws–The Inside Story” and hear Spielberg tell more about the use of the shark (https://oreil.ly/S-aPa).

22 Walter, “Emotional Interface Design.”

23 Hoa Loranger, “Minimize Design Risk by Focusing on Outcomes Not Features,” Nielsen Norman Group, August 14, 2016, https://oreil.ly/aYRiU.

24 Melanie Deziel, “Why Brands Need to Branch Out From Product-Focused Content,” Contently, November 30, 2015, https://oreil.ly/6Yo_a.

25 “Kentico Digital Experience Survey,” Kentico, June 2, 2014, https://oreil.ly/tJlek.